During the Spring 2024 semester, I had the opportunity to learn about and reflect on my inclusive teaching practices through the Protocol for Advancing Inclusive Teaching Efforts (PAITE).

Developed by Addy et al. in 2023, PAITE outlines 16 codes, described below, that can be used to document an instructor’s use of inclusive teaching practices. Over a series of three classroom observations, a trained observer used PAITE to note which methods I personally used during every 10-minute interval of class time. Each observation session was followed by a debrief where I met with the observer to discuss and reflect on the teaching practices that were observed.

All observations were made for COMM 432: Communication, Technology, and Society, an undergraduate class of 35 students. While this was my fourth time teaching this course, it was my first time teaching in a “hybrid” format where we met in person on Mondays and over Zoom on Wednesdays. All observations were conducted during in-person sessions.

I went into the process completely unfamiliar with the PAITE categories but was excited for the opportunity to get detailed, methodical data on my teaching practices. I am deeply passionate about inclusive teaching, but — like many in higher education — my training has largely consisted of 1-off workshops with little formal evaluation or reflection. PAITE gave me an opportunity to quantify the mix of inclusive practices I use over the course of a semester and gave me space to reflect on what kind of inclusive teacher I want to be. I learned a lot about my teaching and was particularly glad to see that I frequently engage in practices of relationship-building, affirmation, using diverse media, and building real-world connections.

The Protocol for Advancing Inclusive Teaching Efforts (PAITE)

As I know from my research in computational social science, all quantitative measures are imperfect. Quantification is, by definition, a simplification of our complex reality. That simplification has the benefit of allowing for aggregation which can reveal meaningful trends and patterns, but it also means that researchers must make difficult and impactful choices as to what phenomena are worthy of being measured, recorded, and aggregated.

Different research questions, motivations, approaches, and contexts will lend themselves to different research choices – leading reasonable researchers to make different decisions as to how to best measure a phenomenon of interest.

I’m not sure I would have made the same choices as Addy et al. (2023) in developing measures of “inclusive teaching,” but the PAITE categories are still extremely useful. PAITE details 15 inclusive teaching practices with a 16th category for “other.” This “other” category turned out to be one of my most frequent and included activities such as moderating full class discussions, explaining the reasoning behind course policies, and outlining each class’ agenda and upcoming deadlines.

While PAITE does not do any formal grouping of the remaining 15 categories, I have come to think of them as outlining 5 relevant meta-categories, which I’ve described with their respective PAITE codes below:

- Assessment: Includes assessing students’ prior knowledge (PRIOR) and asking questions that check students’ comprehension (COMP).

- Community building: Includes developing and implementing community standards (COM), Relationship building (REL), using student names (NAME), and giving verbal affirmations of student contributions (AFFIRM).

- Inclusive examples: Includes providing examples that present a diversity of people and perspectives (DIVEX), using diverse visuals or media for multi-modal engagement (MED), and connecting material to real-world applications (REAL).

- Reactionary teaching: Includes addressing exclusionary or other oppressive acts (EXCL) and avoids making assumptions about specific students’ identity or ability to speak for a group (IDEN).

- Teaching practices: Includes using growth-mindset language to focus on process rather than outcomes (GROW), supporting equitable student participation (EQPART), engaging in active learning strategies (ACTIVE), and allowing students to choose course activities (CHOICE).

A formal list of all categories and their descriptions can be found here.

My Inclusive Teaching Strategies

Figure 1 shows my use of the PAITE-defined inclusive teaching strategies across the three observed sessions. Activities that I consider to be within the same meta-category are stacked together.

The first observation took place on the first in-person day of class, the second took place just prior to the midterm exam, and the final observation took place as the semester was wrapping up.

Variation over time

These distributions reflect, in part, how my teaching naturally changes over the course of a semester. For example, at the beginning of the semester, I focused on community-building but spent no time on assessment. By the middle of the semester, I had begun conducting assessments, particularly engaging in comprehension checks of covered material. While I still engaged in community building at this time, the specific mix shifted from establishing community standards and asking students their names during the first day of class to providing more affirmations of students’ contributions and supporting relationship-building between students by the middle of the semester. By the end of the semester, there was little need for additional community building, and I focused instead on inclusive examples. While throughout the semester, I presented a diversity of people and perspectives, used diverse visuals, and discussed real-world applications, all three of these categories were most prevalent at the end of the semester.

My common teaching practices

Across these three sessions, you can also see the inclusive strategies I engaged with most frequently. Using my own meta-category grouping, my most frequent practices were inclusive examples (39.7% of recorded codes), other (26.6% of recorded codes), and community building (22.5% of recorded codes).

Nearly half (47.6%) of observations in the “inclusive examples” meta-category came from my use “diverse visuals or media” (MED), reflecting my intentional use of images, memes, gifs, and videos in class. Another third (34.8%) came from my efforts to make real-world connections (REAL) between the course materials and life beyond the classroom. I was surprised, however, to see that only 17.7% of my “inclusive examples” (7% of all observed codes) were from presenting a “diversity of people, situations, perspectives, or ideas” (DIVEX). However, after reviewing the observer’s notes and reflecting on my teaching, I think this is in part because I focus on encouraging students to interpret materials through their own perspectives (ie, REAL) rather than imposing outside perspectives.

My students themselves come from diverse backgrounds and perspectives, and I like to give them space to reflect on and compare their diversity of experiences, a practice that generally gets coded as REAL under PAITE. Furthermore, while I am very intentional about covering a diversity of perspectives over the course of the semester (for example, talking about the use of social media by the Black Lives Matter movement, or comparing Goffman’s conception of ‘face’ to the Chinese concept of 面子 (mianzi)), any singular class session tends to focus on a particular perspective rather than comparing a diversity of perspectives. I believe strongly that representing a diversity of people and perspectives is incredibly important to maintaining an inclusive and educational classroom, and whether this is an area for improvement or merely a limitation of the coding, the use of diverse examples something I plan to keep in mind as I prepare my classes in the future.

Across my observed sessions “other” was consistently one of my most common categories. To me, this begins to show some of the limitations of PAITE, at least when applied to my personal teaching approach. In many of my classes, I like to blend lecturing with class discussion – regularly prompting students to engage throughout the class period. At the beginning of the semester, I often structure this as a think-pair-share or small-group exercise to allow students to get to know each other and become more comfortable sharing their perspectives and ideas. Such activities were frequently coded as relationship-building (REL), with my check-ins with individual groups and moderation of full-class discussion coded as other (O).

Additional items coded as “other” included time spent intentionally reflecting on course policies, plans, and expectations. As a first-generation to college student myself, I spent much of my undergraduate career unclear on what was truly expected of me. I worked hard to be a good student, but in retrospect, I didn’t actually know how to be a good student—because no one had ever taught me. In my classes, I therefore spend time discussing topics such as how to engage with the assigned reading, how to take useful notes, and how to study for an exam. I also like to explain my reasoning behind various assignments and course policies—aiming to help students see how the choices I make support their learning and development. These are activities that I consider to be central to building an inclusive classroom, but which PAITE doesn’t fully account for.

My uncommon teaching practices

Figure 1 also gives insight into the PAITE-defined practices I do not tend to engage in. Most notably, across all observed sessions, there were no instances of what I consider to be “reactionary teaching.” This meta-category encompasses two PAITE codes which–thankfully—have never occurred in my classes. I call this meta-category “reactionary” because both codes are predicated on the existence of problematic behavior: either someone in the class engaging in “exclusionary or oppressive acts” which the instructor must then address (EXCL) or the instructor themselves being problematic by “making assumptions about a particular students background” (IDEN). While the “IDEN” code technically reflects instances of the instructor not making those kinds of assumptions, as my observer pointed out, you can’t code for the absence of something. So ultimately, I think it’s a positive sign that neither of the practices were recorded in my classroom.

Perhaps surprisingly, the other meta-categories that appeared infrequently were assessment (6.3% of observed codes) and teaching practices (4.8% of observed codes). I believe the relative sparseness of both of these results from a combination of my intentional teaching choices and how those choices are coded by PAITE.

For example, one teaching practice recorded by PAITE reflects the instructor offering “students the opportunity to choose between different activities” (CHOICE). This code was only recorded once across all my observed classes, but nearly all of my assignments include an element of choice – for major assignments, students can choose their particular topic, focus, and style; for minor assignments, students can typically choose the specific weeks they submit (for example, 4 out of 10 weekly discussion posts are dropped). What I rarely, do, however, is present specific options to the class to vote on as a group or to decide how a class session will proceed. This does come up on occasion, but students rarely agree on what they would most like to do, so I prefer to give students choices on individual assignments or to gather feedback through anonymized surveys. Neither of these activities were captured by PAITE.

Similarly, while think-pair-share and small group discussions were coded as both active learning (ACTIVE) and equal participation (EQPART), full-class discussions were not. While I like to start the semester with these opportunities for students to get to know each other and find their voice, I tend to favor full-class discussions later in the semester. I work hard to ensure that everyone feels comfortable sharing and that I’m creating space for those who speak less frequently. But, I also intentionally do not cold-call on students, which would be required to ensure “equal participation” which PAITE defines as “the majority of students are engaged in an activity.”

Under the “assessment” meta-category, PAITE considers assessing students’ prior knowledge (PRIOR) to require students to submit work. I’ve found that approach helpful in more math or stats-based classes, but I frankly don’t think submitted quizzes or other prior knowledge assessments would be particularly useful for this class. I often kick off a discussion by asking students to define or give examples of a particular course concept – I find that a useful jumping-off point for guiding the conversation, but I see little value in conducting this as a formal assessment. PAITE does not require comprehension checks (COMP) to be submitted, however, and I did see that, after the very start of the semester, I did have these kinds of checks regularly sprinkled in.

80 Minutes of Inclusive Teaching Strategies

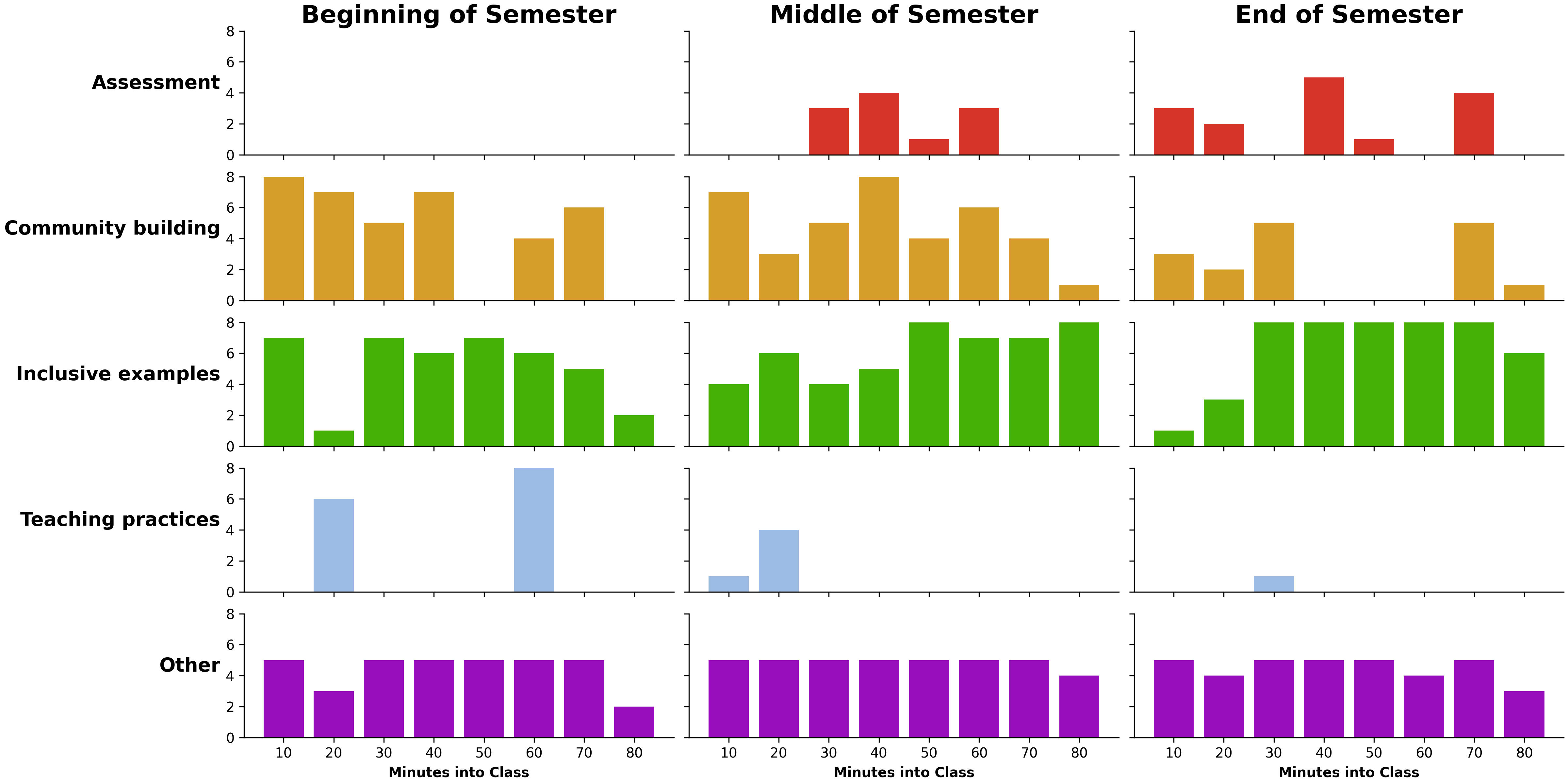

Figure 2 shows, for each observed class, how I distributed my teaching strategies across the 80-minute session. For visual ease, I have grouped PAITE code into the meta-categories, dropping the category that never appeared (reactionary teaching).

Most notably, this shows that my most common teaching practices – community building, inclusive examples, and other are generally evenly distributed across the class period. These are not only activities I engage in frequently but are practices I turn to regularly and consistently.

Assessment and teaching practices, however, tend to be more periodic and highly dependent on the time of year. At the beginning of the semester, I have active learning activities spaced out as two core foci of the session. Later in the semester, I continue to engage with teaching practices such as approaching work with a growth mindset or ensuring equal participation, but this becomes rarer as I see students getting to know each other and getting comfortable speaking up in class. Assessment, reasonably, has the inverse trajectory – I don’t assess students on the first day of class, but I regularly ensure comprehension checks as we go through the material for later classes.

Final Reflections

Having an outside observer record PAITE codes for my class was extremely helpful and has given me a lot to think about as I aim to continually improve my teaching. One of the first questions I had for my PAITE specialist was “what does good, inclusive teaching look like?” But, of course, there is no singular answer to that question. And the answer is not, as I had initially thought, “more of all the codes.”

Rather, good, inclusive teaching means engaging with a mix of strategies and appropriately altering that mix based on a class’ students, learning outcomes, and time of the semester. After reflecting on these observations, I am proud of the work I do to create an inclusive classroom and I am more confident in the decisions I make to do so. I think it’s important to help students connect their knowledge to the real world, to realize how much knowledge they already have from their own experiences, and to regularly affirm the contributions they make and the future ahead of them. I also believe that building a strong, inclusive, class community by discussing community standards and encouraging relationship-building helps students learn better and feel more comfortable learning.

And, finally, while it’s not recorded by PAITE, I think it’s important to spend time teaching students how to engage actively and successfully in their own education. Particularly now, as students are still recovering from years of virtual education, students need to learn how to be students – not only for their time in college, but for their future lives as informed citizens.

After learning more about the coding specifics of PAITE, I am comfortable with the balance of practices I engaged with over the semester. But, of course, there is always room for improvement and there are several key areas I plan to reflect on more in my future teaching. First, I think it is absolutely essential for instructors to present a diversity of experiences, people, and perspectives. I already do this intentionally throughout my classes, but these observations have shown me this is something I can do more of. Second, I plan to do more reading about the various teaching practices recorded by PAITE – using growth mindset language, engaging students in active learning, and ensuring equal participation. These are strategies I know of but am not deeply familiar with. I do not believe that it is necessarily a problem that PAITE recorded these strategies as relatively sparse in my teaching, but I do think this presents a potential direction of learning and growth as I continue to refine my inclusive teaching strategies.

There is no singular answer to what “good, inclusive teaching” looks like, but – thanks to the work of my PAITE of observer and this OTEAR program, I am more confident that I am doing a good job of building an inclusive classroom. These observations have given me new insight into strategies for naming, identifying, and implementing inclusive practices. In doing so, this experience has better equipped me for the continual journey of pedagogical improvement.